A “finite resource” in danger: space debris are increasing by the hour

Millions of pieces of space junk orbiting the Earth are transforming space exploration a more dangerous activity and putting in jeopardize access to Space for future generations. This is not a new or recent problem, but it is becoming "one of the biggest challenges of our time".

Since Sputnik debuted in 1957, humans have been launching satellites into orbit to perform various functions. In total, around 9.000 satellites were established in the past six decades, including Vanguard 1 – the oldest satellite still orbiting –, the Russian Mir space station – deorbited in 2001 –, the Hubble, the International Space Station, the 9 Copernicus’ Sentinel or the 24 Galileo satellites and more recently the more than 2.000 Starlink satellites. Together they provide communications, broadcast television, weather forecasting, and precision farming to maximise crop harvesting and rotation. In addition, they are a fundamental tool for tackling climate changes, among so many others functions.

“And most of the objects that we launch don’t come back”, says Moriba Jah, associate professor at the University of Texas, Austin, and a space environmentalist with a mission of raising awareness about the consequences of space debris for life on Earth. Inoperable human-made objects, including abandoned satellites, pieces of broken satellites, rocket stages, nuts and bolts left behind by astronauts, are accumulating in Earth’s Orbit for decades and are becoming a growing source of unease.

Space debris or space junk is not a new concept or a recent menace. Still, as humankind becomes increasingly reliant on Space-based capabilities and life on Earth increasingly dependent on space-based infrastructure, the subject is becoming “one of the greatest challenges of our time”, as stated by Ricardo Conde, president of the Portuguese Space Agency.

There is a risk that some orbital “highways” will become ususable. © ESA

There is a risk that some orbital “highways” will become ususable. © ESA

“Europe is taking the lead in ensuring Space Sustainability to avoid that space debris become a source of disruption to our economy, way of life and well-being”, says Ricardo Conde, sustaining that Portugal has been supporting “the need to develop systems that allow the management of space assets, control, and monitor objects to avoid collisions”. “Besides causing damage to operational satellites, these collisions can lead to space non-sustainability”, Mr. Conde warns.

Especially since Space, and near-Earth Space, must also be looked at as a “finite resource”, notes Moriba Jah. “Multiple participants are utilizing without coordination, planning, or talking to other people about how they’re using it. As a result, the finite resource and its ability to provide to all the participants becomes exceeded”, he adds.

With the steady growth in the amount of space junk, there is a risk that some orbital “highways” will become unusable. “Unless we start doing something about coordination and planning and behaving in ways that minimise the preponderance” of these space-polluting objects, as the space environmentalist argues.

“The will to act is there”

Some figures prove the urgency of this issue. According to the European Space Agency (ESA) Space Environment Report 2022, “more than 30,000 pieces of space debris have been recorded and are regularly tracked by space surveillance networks”. But the “real number of objects over one centimetre long is probably more than one million”, warns the agency.

Holger Krag, head of ESA’s Space Debris Office, believes that “the world is ready“ to take actual steps to prevent and solve this problem that could deprive “future generations of the use of space”. “Thirty years after the Inter Agency Debris Coordination Committee was formed and 20 years after the first debris prevention guidelines have been issued, all Space faring nations are aware of the problem. The will to act is there, and many Space faring nations have adopted the debris prevention guidelines as their national law”, he frames.

But even if there is a will to act, Holger Krag points out, “internationally binding agreements are still not very near”. Added to this are the “technical challenges have to be tackled since the success rates in preventing debris are still poor“. “This is often a result of limited technical reliability, an area for which we want to provide solution through the Space Safety Programme.” Proof of this is the inauguration of ESA’s new Space Safety Centre, which began operating last April.

European care is also a national concern. In 2008, Portugal joined the ESA’s Space Situational Awareness programme and confirmed its interest in this area in 2019, with the Portuguese subscription to the Space Security Programme at the Ministerial Summit of the European Space Agency (Space19+), in Seville. In this domain, the Portuguese Space Agency has focused on Space Weather, Planetary Defence and, of course, Space Debris.

A business opportunity?

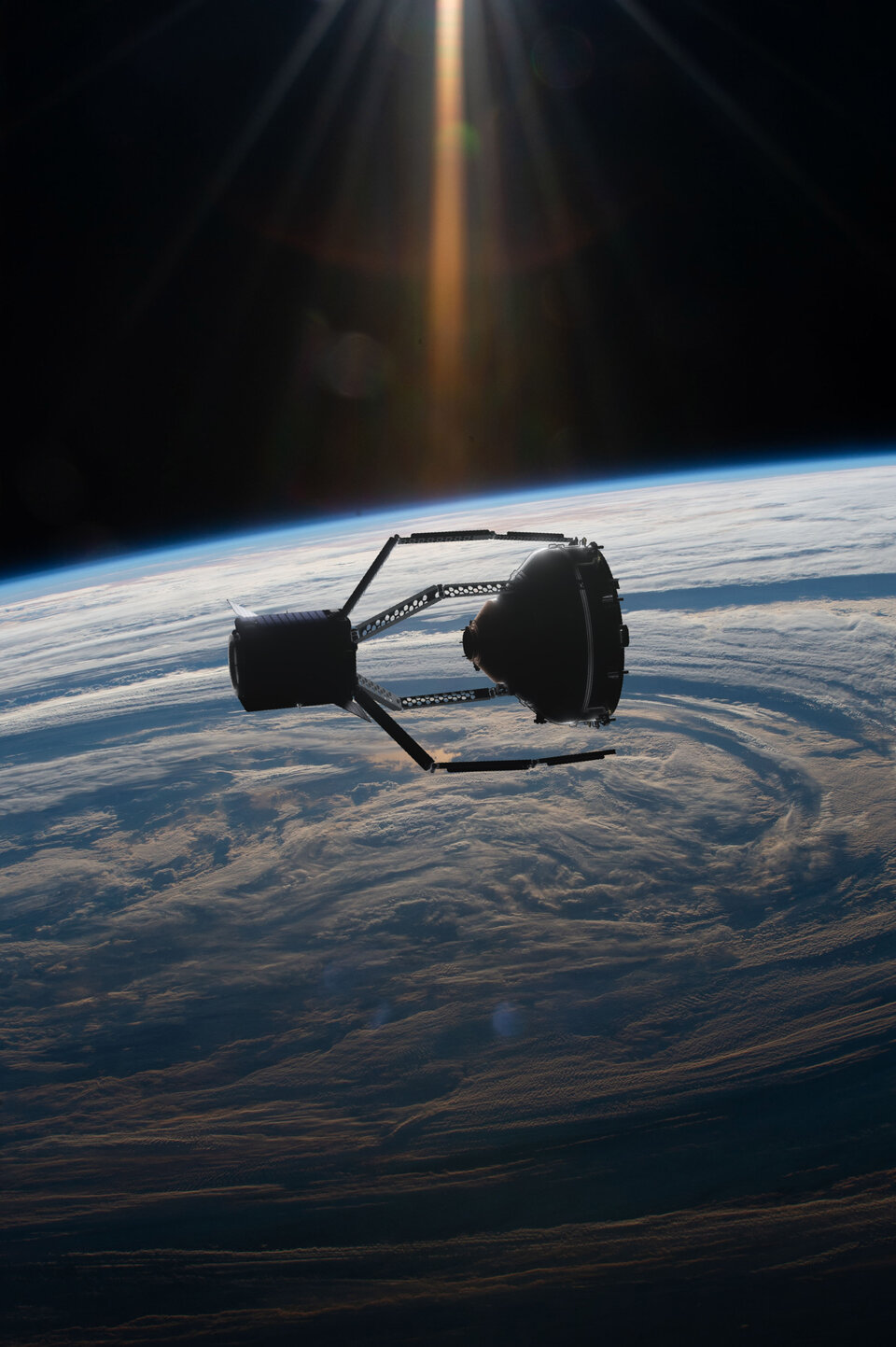

ClearSpace-1 (CS-1) is one of the ESA missions with a significant Portuguese presence, with national industry taking a leading position in the technological developments of services in orbit. The launch of the mission is scheduled for 2026. “ESA has set up the Clearspace-1 mission as a commercial service development from the start“, explains Holger Krag.

The ClearSpace-1 mission will collect, capture, and transport a payload adapter named Vespa to re-enter the atmosphere. Once collected, both the ClearSpace-1 satellite and the Vespa, weighing about 100 kg and the size of a small refrigerator, will be destroyed on re-entry into the atmosphere.

As the name implies, the challenge is to clean up Space – especially by removing larger debris from orbit. Companies such as Deimos Engineering, which partnered with Lusospace and ISQ, and Critical Software are taking part in the mission and leading roles in guidance, navigation, control and flight software.

It is like a double-edged sword: while space debris presents risks for space exploration – and even for astronomy – and the active removal of debris still has a long way to go, space debris management is a significant opportunity.

ESA’s ClearSpace-1 mission’s goal is to remove larger debris from orbit. © ESA

ESA’s ClearSpace-1 mission’s goal is to remove larger debris from orbit. © ESA

The recently created Neuraspace focuses on space junk management and collision prevention between satellites and promises to become one of the new Portuguese unicorns. Founded by Nuno Sebastião, the start-up was incubated at Instituto Pedro Nunes, is part of ESA BIC Portugal and has developed an Artificial Intelligence platform that monitors space debris and prevents collision between satellites (Read more).

While in Portugal, Neuraspace is led by the Italian-German Chiara Manfletti, there is a Portuguese working in the same area in Germany. The Space Systems engineer Luísa Buinhas cofounded Vyoma. The German company was born from the “genuine desire to work towards space sustainability” and a “deep mutual respect” between all those who helped found Vyoma: “We shared a vision of how the future of Space should be, and this drives us every day to achieve this goal.”

The background of some team members, who have worked at ESA and were able to “witness first-hand how space debris affects missions” or “how current operations can be made more efficient with more information and automation” helped Vyoma position itself in the market. In turn, Luísa Buinhas developed “space mission studies for the German aerospace agency”, the Deutsche Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR) and previously specialised “in optimisation of satellite constellation manoeuvres”.

The space systems engineer says there is “an opportunity in managing traffic in orbit” as “there is more and more congestion, due to existing debris, between objects that were generated from collisions in the past and inactive satellites, and due to new constellations that are launched week after week”. “We live in a world that is increasingly dependent on space services at the same time that we have reached a tipping point: space is simply becoming too dangerous to navigate safely,” warns Vyoma’s co-founder.

Thus, the company’s goal is to “solve the challenge of space sustainability by monitoring space debris from space”. Luísa Buinhas adds that Vyoma will launch “a fleet of space cameras that can precisely determine where the debris is in relation to other satellites”. “We combine the data from our cameras with Machine Learning to provide safe and automated satellite operations to an industry plagued with inefficiencies and data uncertainty,” she adds.

Space as a natural resource and a common good

As well as worrying the industry, the Space Debris problem affects human activities beyond space exploration. “We can see Space as a natural resource. Some services fundamentally depend on this medium that people, on the whole, don’t realize: weather forecasting, broadcasting television, or internet services. Without satellites, not even airplanes can fly”, Buinhas points out.

And “nothing guarantees” that space infrastructure, on which many technologies depend, won’t be hit by “a piece of debris”, and so “we could lose that capability”, Moriba Jah recalls.

“And as the number of objects in Space increases, the amount of light reflected from those objects in general increases as well. That makes it harder to detect things like asteroids and anything that could collide with Earth – and even wipe out humanity,” the University of Texas professor warns.

Still, Moriba Jah believes there is “some hope” – “Or I wouldn’t be doing this work.” But this compels cooperation and mutual aid: “I believe it is possible to gather empathy across humanity and encourage compassion to resolve these issues.”