In Portugal, Astronomy is an expanding universe

In December 2000, Portugal became a Member State of the ESO. Since then, astronomy has been growing in Portugal, where academia and industry have both increasingly participated in relevant international projects.

José Afonso was not yet 10 years old when a book opened his fascination for the universe and the questions that dwell in it. “The last pages had the sky map. I began to identify the stars and constellations and I found it fascinating how far away they are and what they might hold,” says the co-founder of the Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences (IAstro) and researcher at the Faculty of Science of the University of Lisbon (FCUL).

The cosmos can be like that: the pages of a book were enough to influence someone’s path. The sky and the dance of the celestial bodies were enough for humanity to find solutions and answers over the centuries. The quest for knowledge about the universe is not a recent phenomenon and long predates the invention of the telescope in the 17th century – after all, it was by observing the stars that humans were able to identify different seasons millennia ago and, with that, bring the practice of agriculture to a new level.

There is still much to learn, but “knowledge of the universe has been accelerating in the last few decades.” And “the questions that arise today are different from those that arose 20 years ago: we have new technologies, new observation capabilities in all wavelengths. So many doors are opening,” José Afonso points out.

What does this mean for Portugal? The IAstro co-founder believes that Portugal’s joining the European Space Agency (ESA) and the European Southern Observatory (ESO) in 2000 were key moments for the country’s consolidation in that sense. “At the beginning of this century we reached a point of recognition on a par with any other country, and we have been increasing that position. We have participated in some of the consortiums at the forefront of astrophysics,” he says. In truth, Portugal’s accession to the ESO (like the process for joining ESA) was the culmination of years of work. It began in the second half of the 1980s, when Teresa Lago, full professor and founder of the Astrophysics Centre at the University of Porto, prepared the proposal for Portugal to join the organisation.

On 10 July 1990, Portugal and ESO signed a co-operation agreement, aimed at full Portuguese membership of ESO within 10 years. © ESO

The Cooperation Agreement with the ESO, signed in July 1990, guaranteed Portugal “observer status” and defined a transition process for it to become a full Member State. It would take ten years for Portugal to formally request membership as a Member State, which eventually happened in December 2000. Portugal contributes annually to the operating costs of the ESO; in exchange, this brings the possibility for Portuguese research teams to have access to scientific participation in Astronomy and Astrophysics projects.

“Portuguese participation opens up the possibility of being part of wider programmes. It is worth the investment in these programmes; the countries that invest are entitled to a number of nights for observations in the ESO telescopes, which is very good,” explains António Amorim, a professor at the Faculty of Science of the University of Lisbon who is also the Portuguese co-investigator of GRAVITY, the second generation instrument of the Very Large Telescope Interferometer (VLTI) of the ESO.

An expanding universe

For Alexandre Cabral and Manuel Abreu, also from IAstro, “it is difficult to distinguish one or two moments of special relevance for the Portuguese community working in Astronomy, Astrophysics and Space, especially because it has developed over many years” – but it is inevitable to mention moments such as PoSAT (the first Portuguese satellite) and the accessions to ESA and ESO.

Then in 2005, another project marked the national path in the fields of astronomy. CAMCAO – Camera for Multi Conjugate Adaptive Optics – was “the first Portuguese astrophysics instrument,” says António Amorim. Commissioned by the ESO, CAMCAO was the first high-resolution infrared camera with a wide field of view to be used with adaptive optics – and “it had all the vicissitudes of a beginner.” Good thing: then, the expertise acquired in the early 2000s with CAMCAO allowed a Portuguese team to also integrate GRAVITY, for which “there was a need to make an infrared camera.”

Signing of the Portugal-ESO Agreement on 27 June 2000, at ESO Headquarters in Garching, Germany. © ESO/H. Heyer

In ESA, as well, the academic community and industry have been participating more and more in scientific programmes. Some of these are in the implementation phase, while others are already in operation, such as the PLATO, EUCLID, ARIEL, CHEOPS, GAIA or LISA projects. “In ESO, which will eventually have a more recent participation in the development of instruments, we would highlight ESPRESSO, MOONS, ALMA, GRAVITY and the recent involvements in the instruments of the future ELT, METIS and ANDES,” Alexandre Cabral and Manuel Abreu add.

Portuguese membership in the ESA and the ESO also brought the experience to know that “astronomy is not just using telescopes and understanding what they are revealing to us,” underlines José Afonso. To do “good science with an impact, we have to be involved in the construction of the telescopes.” Therefore, the IAstro co-founder believes that “it is essential to have the ability to be part of an international consortium, participating in the scientific definition of what will be done, but also building part” of the technologies that will be used.

Portuguese companies increasingly participate

Alexandre Cabral and Manuel Abreu agree on the evolution of Portuguese participation in these areas of knowledge, speaking of a “relevant growth with the multiplication of participations in ESA missions and instruments,” but they acknowledge that they do not know if there is “a recent accounting of the number of people, universities and companies with clear links to this area of knowledge.”

While the academy has grown in “scientific and applied development capacity,” companies have also “demonstrated a greater technological readiness in many of the technologies relevant to Astronomy and Astrophysics, both in flight instruments and in instruments based on ground-based observatories,” indicate Manuel Abreu and Alexandre Cabral. The two researchers also note that there has been “an increase in mutual recognition in terms of respective skills and capabilities” between academia and industry.

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) Observatory is a good example of the need to unite theory and practice in order to open even more doors to knowledge: “SKA is a revolutionary idea. It takes what is known today and asks: ‘What if we have a technology that is 100 times better? What can we achieve?'” introduces José Afonso. With the SKA, which will be the largest telescope ever built, “a revolution in knowledge” is expected – and this includes more information about “the formation of stars and planets,” but also of “more distant things” such as “research into the first galaxies or the first gas that exists in the universe.”

© SKAO

And Portuguese companies have been present in this quest for knowledge of the universe: “There has been an effort over recent years, and companies are increasingly awake to this scientific and technological development, because there is nothing more demanding than knowledge of the universe.” Moreover, Portugal is one of the founding members of SKAO, which allows national research centres and industry to be closely linked to the development of the telescope network – so much so that recently two Portuguese companies and a college were awarded contracts worth 3.1 million euros to participate in the development of the structure’s software.

“The Portuguese participation in a leading position in several projects shows the quality of national academia and industry. And not only are they at the forefront of important scientific projects, as is the case of SKAO, but they also stimulate the development of technological capabilities in these areas in the Portuguese space ecosystem,” says Cláudio Melo, responsible for Science projects at the Portuguese Space Agency.

But the contribution of Portuguese industry in relevant projects in these fields is not limited to a single case. ISQ is one of the Portuguese organisations with several examples to give. The Oeiras-based research centre included aerospace engineering in its range of areas of activity in 2003 and participated in ALMA (Atacama Large Millimetre/submillimetre Array), a telescope operating high up on the Chajnantor plateau in the Chilean Andes, which searches for our cosmic origins.

“There has been a continuous intervention in the ELT [Extremely Large Telescope]. ISQ has been involved from the very beginning, even in the phase prior to the start of the manufacture of the main components,” says Paulo Chaves, responsible for the aerospace area of the centre. “This participation occurred, first, with the work carried out from Portugal, and then in a second phase with the permanent team in Garching,” at the ESO facilities in Munich, Germany. This team accompanies the ELT “not only at the base level,” but also follows “the design, integration and assembly processes.”

With eyes on the MOONS

For José Afonso, the strong involvement of Portuguese academia and industry in scientific projects happens for a very simple reason: “We have managed to be involved in several missions because we effectively have that capacity.” In addition, this “competence and professionalism” has been accompanied “by the reinforcement of confidence of European partners that recognise the capacity and quality of the Portuguese contribution,” emphasise Manuel Abreu and Alexandre Cabral.

“This increase in collaboration in consortia and scientific missions is only possible when framed within a funding strategy that recognises the importance of such participation, but above all the long-term nature that characterises these missions, often beyond normal political cycles,” the researchers also emphasise.

Portugal has been reinforcing its institutional support for the development of space sciences. In the last two ESA Ministerial meetings we increased our subscription to the ESA PRODEX programme, for example. “And it is through this programme that we have been able to support national participation in the development of instrumentation for ESA’s scientific missions,” says Claudio Melo. In November 2019, Portugal placed €3 million into the envelope that finances the industrial development of scientific instruments and experiments, as compared with the 750,000 euros subscribed in 2016.

This stability is welcome and necessary since programmes are outlined years in advance of their implementation, in both terrestrial astronomy and space missions, to the extent that each instrument “defines knowledge in the next 10 or 20 years.” Preparing them for the operationalisation phase is a lengthy process that requires the delivery and commitment of all parties.

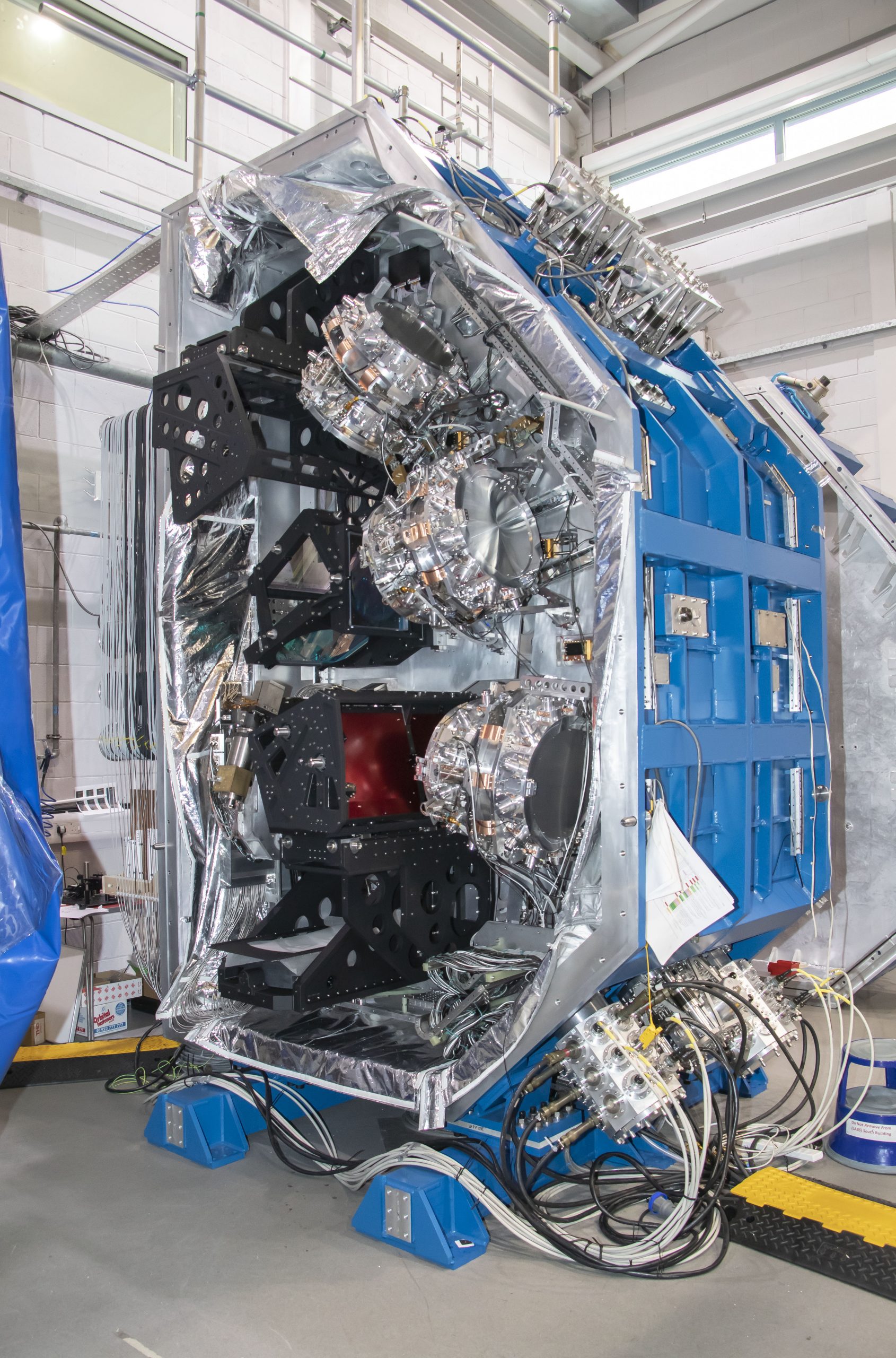

An example of this is the MOONS (Multi-Object Optical and Near-infrared Spectrograph). The instrument will be installed in the VLT “and will be able to observe up to 1000 galaxies, in detail, at the same time.” José Afonso summarises that “it is not just about obtaining the image of the galaxy, but also the spectrum, which will give information about the physical processes that are taking place at a given moment.” Basically, the aim is to “get to know the nearest universe around us in some detail.”

MOONS’ construction is nearly constructed. © DR

One of its main components, the field broker, has been developed by researchers at IAstro. José Afonso, co-principal investigator in this project, explains that the process dates back to 2009: “It was designed, proposed, accepted and has been developed and built by us, in Portugal. The component is responsible for the image quality of MOONS; it ensures that the image quality is very good in all observation.” Next year, the component will be taken to Chile to be installed on the VLT. Then, from 2024, “five years” of intensive use for observation and study will follow.

There will be many nights ahead. After all, the aim is to “observe half a million galaxies at a distance of 6 to 7 billion light years, and be able to understand what the galaxy population was like at that stage.” For someone like José Afonso, who discovered a fascination with the universe in the last pages of a book, this will not be a difficult task. More than that, participation and contributions like this not only push for “technological development” but also allow Portugal to have “a very strong word in astrophysics” and other branches of astronomy.